Until the end of the nineteenth century, the production of nemas (barkcloth) was found widely distributed around island of Erromango.

Nemas was made from a number of different types of bark. Each bark was used for different purposes depending on its type, quality and colour. Barks were cut off using a machete (after European contact) and strips would be rolled up and then soaked in water overnight. The bark was then placed over a long round log called nampou for beating.

Most of the nemas production was done by women. Two females would sit next to each other sprinkling water onto the bark to maintain its moisture during the beating process. Different types of four-sided barkcloth beaters would be used at different beating stages: first, for beating the first bark strips for a long period of time; second, for beating different layers to expand and thicken the cloth; and third, for joining the bark strips until the desired size was made. The barks were then hung and left to dry. (Huffman, 1996:138 information from James Nobuat Atnelo). Once the bark was completely dry, the decorating process began.

Erromango nemas had utilitarian, ceremonial, and status uses in exchange and ritual. Decorated nemas, was mainly for ceremonial use, display, trade, exchanges, bride-price payments, clothing and in death to wrap the person’s body.

The type of barkcloth needed determined the type of bark used and this also depended upon ceremonial use. The beautifully decorated n’mah neyorwi, worn exclusively over the shoulders by high-ranking women, the wives of the paramount chiefs and worn at large festivities, was made of noma bark. A n’mah neyorwi, could display clan designs indicating women’s status and prestige within their own community (Yvonne Carrillo-Huffman, information from Jerry Taki Uminduru, 2002). Undecorated barkcloth had a more functional role such as carrying babies and as blankets to protect from the cold.

Specific designs represented on nemas are still strongly interwoven with people’s ancestry, cosmology, and their relationship with the natural and spiritual world. The representation of some ancestor/spirit guardian figures become testimonies of clan identity, narrating their clan origin and history and are also linked to land rights demarcations. Traditional designs are mainly pictorial but also include geometrical imagery. Marine fauna most commonly represented are types of fish, turtles and whales, whilst lizards and geckos commonly represent land fauna. Culturally important are trees, leaves and flower designs associated with guardian spirit-figures.

The dye used in Erromango traditional barkcloth decoration was obtained by mixing nohorat tree bark with ashes and water. A yellow turmeric colour and red was obtained from different roots. White colour was obtained from burning coral from the reef.

In Erromango, there are strict social prohibitions with regard to sharing knowledge of clan designs and associated narratives linked to traditional political structures and land rights. Therefore, the ancestor stories passed on orally representing specific designs are strictly limited to those with relevant clan rights. (Yvonne Carrillo -Huffman information from Jerry Taki Uminduru, 2008).

The lengthy missionary stay of the Presbyterian missionary H.A. Robertson and his family on Erromango from 1872 to 1913 proved to be the most highly effective of all the missionary assaults on the island and it was also the most successful in the destruction of Erromango culture. Nemas production and use as a major mark of clan identity was severely dislocated, and many important ritual objects were destroyed or taken to overseas museums.

Decorated barkcloth production plays a key role in safeguarding traditional knowledge and local identity, and the continuing strength of the oral traditions also become fundamental in the process of reawakening barkcloth production .

The Australian Museum holds one of the world’s largest collections of Erromango barkcloth and has been the first cultural institution outside of Vanuatu supporting the process of revival of Nemas production. In 2002 photographs of the Australian Museum’s early Erromango collection were presented to Chief Jerry Taki Uminduru and a delegation of Erromangans gathered in Port Vila, Vanuatu.

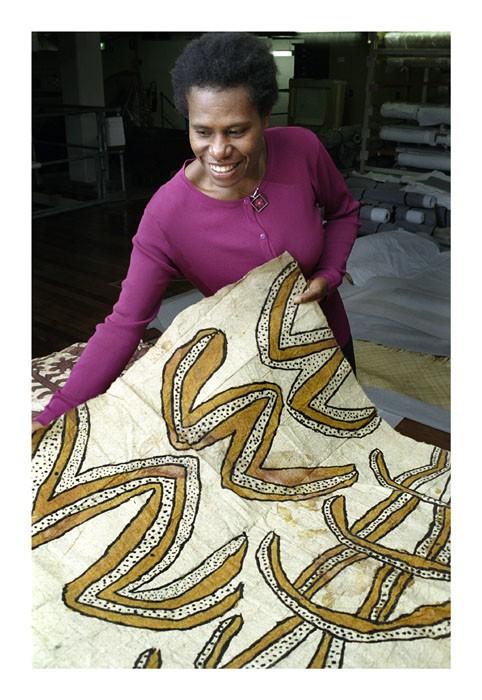

This was followed up in 2003 with a visit by Sophie Nemban, female Erromangan, Vanuatu Cultural Centre fieldworker to engage and study early women’s cultural objects at the Australian Museum. In 2006, Chief Jerry Taki, visited the Australian Museum to document men’s early cultural material. These visits resulted in a new stage of cultural activism in the process of strengthening culture and barkcloth production back in their island. In 2008, examples of some of newly-made decorated nemas from all over Erromango were shown at the Umponielongi cultural festival, Umponielongi, southern Erromango. A collection of these new nemas were made for the Australian Museum.

Sophie Nemban from Umponielongi, South Erromango, fieldworker from the Vanuatu Cultural Centre for Erromango examining a decorated Nemas, Australian Museum Collections,

Sophie Nemban from Umponielongi, South Erromango, fieldworker from the Vanuatu Cultural Centre for Erromango examining a decorated Nemas, Australian Museum Collections,

Sydney, 2003.

Photo: James King, Australian Museum (2003)

Further reading

Carrillo-Huffman, Y. (2008). The revival of Nemas: Reconstructing Erromangan traditions. Explore: The Australian Museum Magazine, 30 (4), 24-26.

Carrillo-Huffman, Y., Chief Jerry Taki; Nemban, S. Nelokompne Rises Again. 35 minutes film documentary spoken in Bislama, subtitles in English. Filmed on Erromango (2008) Edited and released (2009).

Carrillo-Huffman, Y. (2010). Pintando con los ancestors: renacimiento e identidad de la tela de corteza… (Painting with the ancestors: barkcloth revival and identity. Indigenous perspectives on Maro paintings from West Papua, Indonesia and Nemas, Erromango, Vanuatu). In C. Mondragon (Ed), Moana: Las culturas de las islas del Pacifico (pp. 73-90). Mexico, Instituto National de Antropologia e Historia, Ciudad de Mexico.

Carrillo-Huffman, Y., Taki Uminduru, Chief Jerry & Huffman, K. (2013). Erromango Nemas: Indigenous Knowledge, Engagement and the Role of Museums in Cultural Reactivation. In Mesenholler, P. & Lueb, O. Tapa, Art and Social Landscapes, Made in Oceania (176-197).

Goodenought W. (1963). Cooperation in change: An anthropological approach to community development. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Huffman, K. (1996). The “decorated cloth” from the “Island of Good Yams”: Barkcloth in Vanuatu, with special reference to Erromango. in J. Bonnemaison, K. Huffman, C. Kaufmannn & D. Tryon (Eds.), Arts of Vanuatu (pp. 129-140). Bathurst: Crawford House Publishing.

Hughes, T.D. (1985). The effects of missionization on cultural identity in two societies. In F.A. Salamone (Ed.), Anthropologists and missionaries, Part I. Collected works, studies in third world societies (pp. 167-182). Williamburg. VA: Colleage of William and Mary.

Lawson, B (1994). Collected curious: Missionary tales from the South Seas. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Lorde, A. (1984). Sister outsider. Berkeley: The Crossing Press.

Nakata, M (2007). Disciplining the savages, savaging the disciplines. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Robertson, H.A. 1902. Erromanga: The martyr isle. J. Fraser (Ed.). London: Hodder and Stoughton.