One of the most popular and noteworthy objects in Papua New Guinea must be the bilum or the looped netbag or stringbag as it is also referred to. Both in the past and in the present, the bilum is stated to be one of the most culturally sig¬nificant objects in Papua New Guinea (Andersen 2015: 16). Made predominantly by women “but carried by everyone, they are a notable example of indigenous material culture that has persisted – indeed, flourished – in the face of introduced technologies” (cf Andersen 2015: 16; Garnier 2009). The bilum has many local names, functions, shapes and sizes and carries everything from garden and market produce to private belongings, such as wallets and mobile phones, to newborn babies. Moreover, they are also used as “attire, dancing regalia, amulet, toy, trade commodity, wealth item, marker of identity, spirit catcher, shrine and source of all cultural resources” (MacKenzie 1991: 6). Before wool and nylon string became available and popular, stringbags were made with natural fibres, such as the inner bark of the siria tree (Gnetum gnemon – Gnetaceae), which has been used in PNG’s Oro province for making stringbags (Gnecchi-Ruscone 2016). Here, women strip the bark off the plant, remove the outer layer and beat the softer fibres before leaving them in the sun to dry. They then tear the fibres and use the palm of their open hands to make a three-ply string, by rolling the fibre up and down their calf. Traditionally, the string is left undyed, or is dyed with black or red pigment. Today women use a combination of bush and store-bought dyes instead of making the dyes from organic materials (Gnecchi-Ruscone 2016). By using a looping technique, the strings are knotted together to form a bilum (for a detailed discussion of the looping technology see: Baker 1985; Sillitoe 1988; MacKenzie 1991).

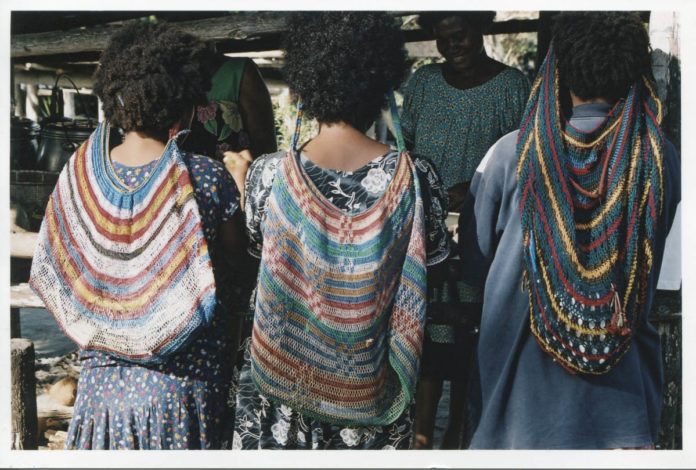

Stringbags have become increasingly colorful (see photo 2) and modern and recently have been embraced in what Nicolas Garnier (2009) calls “bilumwear”: dresses, skirts and blouses made with the looping technique that are “worn proudly to graduation ceremonies, cultural shows, political speeches, and other public events” (cf Andersen 2015: 17; Cochrane 2009). In a recent article on stringbags in the Papua New Guinea Highlands, Barbara Andersen (2015: 16) argues that the bilum is more than a ‘container’ that signifies complex meanings about gender (see MacKenzie 1991), as it increasingly indexes ideas about geography and social location. Especially for young PNG women, the bilum has become a “transporter” that is intertwined with their desires, imaginings, and their “pursuit of cosmopolitan goals of mobility and freedom” (Andersen 2015: 16, 20).

References

Andersen, Barbara 2015. “Style and self-making. String bag production in the Papua New Guinea Highlands.” Anthropology Today Volume 31, No 5: 16-20.

Baker, Sylvia 1985. Make your own bilum: the craft of knotless netting of stone age origins and including thigh spinning in the primitive manner. Brisbane: Boolarong Publication.

Cochrane, Susan 2009. “Bilum breakout: Fashion, artworld, national pride.” Artlink 29(2): 64-67.

Garnier, N. 2009. Fashion and bilum, from tradition to modernity, from individual creation to collective achievement.

Gnecchi-Ruscone, Elisabetta. 2016. “The extraordinary values of ordinary objects: String bags and pandanus mats as Korafe women’s wealth?” In Sinuous Objects. Revaluing Women’s Wealth in the Contemporary Pacific, edited by A. Hermkens and K. Lepani. Canberra: ANU E-Press, 115-136.

Sillitoe, Paul 1988. Made in Niugini: Technology in the highlands of Papua New Guinea. London: British Museum Press.

MacKenzie, Maureen A. 1991. Androgynous Objects: String bags and gender in central New Guinea. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers.