Kanthas are vibrant patchworked quilts, recycled out of layers of used and discarded fabric, made by rural women in the eastern part of India. They were born out of need- to protect from cold. Kanthas were visual diaries of the maker, who transformed them into exquisite pieces of hand-embroidered art called the Nakshi Kantha during their leisure time. The word ‘Kantha’ (pronounced variously as Kantha, Kaentha, Keta, Ketha, Kheta) has no discernible etymological root. It originated from the Sanskrit word ‘Kontha’ meaning ‘rags’ and perhaps substantiates the recycled fabrics used for making them. Another source mentions its connection with the term ‘Kontha’ that refers to the ‘neck’ of Lord Shiva and has a mythological connotation.

The origin of the craft goes back to the pre-Vedic period where monks used them as wrappers. Krishnadas Kaviraj offered the first written document of a Kantha in his 500-year-old book entitled Sri Sri Chaitanya Charitamrita. Sebastian Manrick referred to such quilts in his travel documents. He noted that these were exported to Portugal in 1629 by the East India Company and were in great demand in Europe. Quiltmaking was popular in the eastern states of India, particularly in Bengal, Orissa, and Bihar. However, the Nakshi Kanthas of undivided Bengal became the most popular and revered for their intricate motifs on a rippled ground.

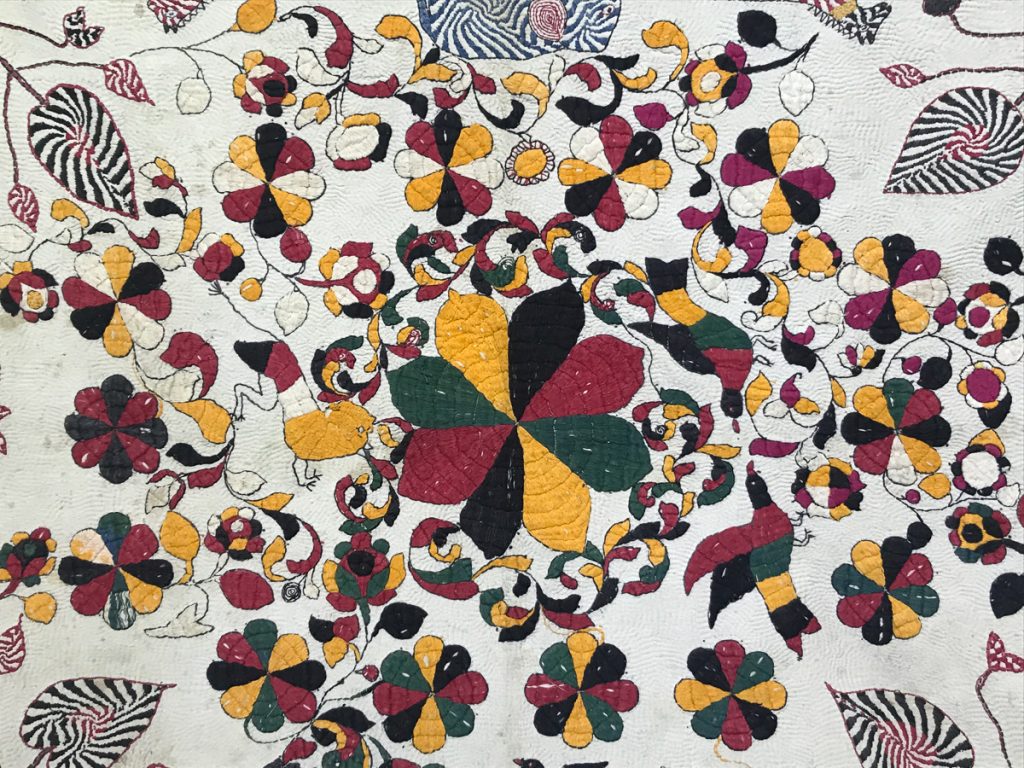

Kantha is an embodiment of recycled craft made out of used and discarded sarees (unstitched draped garment worn by women over a blouse and underskirt) and dhotis (draped and unstitched lower garment for men). The treads used in the woven borders of these sarees were drawn out and used for the colourful embroidery. The art of Kantha making involved layering of fabrics and holding them together with intricate running stitches that rendered its characteristics ripple effect. Traditional Kanthas had Nakshas or motifs with colourful threads on a white background representing the local flora fauna and objects of daily use. As these motifs were not drawn or traced, they bore an unscaled crudeness and were two-dimensional. It is the most sustainable form of craft as it uses no tools or machines. Kantha artisans work during the day using sunlight. A wooden frame, hand needles, recycled fabrics and threads are all they use.

Kanthas took months to make and was considered a community craft. It brought together women of the Hindu and Muslim communities, who often worked on a single piece. Later, following the partition of Bengal, these communities developed their distinctive style of Kantha making. For instance, Muslims were not allowed to embroider human or animal forms and preferred floral and geometric patterns. Hindus had no such exclusions. These restrictions do not prevail anymore among the Kantha artisans. The quilts made for a ceremonial purpose to give to a newborn or as dowry bore symbolic motifs. The central lotus was used commonly in most quilts and often had numerous petals. Fishes, horses, elephants, human figures, trees of life, birds were stitched randomly with beautiful borders surrounding the edge of the quilt. Frequently meaningful poems and verses were embroidered onto them. Some had the name of the maker stitched on them as well. These quilts not only documented the creative skills of women, alongside their socio-cultural narratives that were interlaced into the cloth to pass on as a valuable legacy.

The art of Kantha making is passed on from the mother to the daughter even today. Post-independence, the craft was used as a tool for refugee rehabilitation and employment generation among rural women. Since commercialisation which came about in the late 1940s, the craft has undergone a sea change. Rabindranath Tagore, the Nobel laureate and his daughter-in-law played a pivotal role in helping local women adopt this craft as a source of livelihood. Therefore, we find an abundance of Kantha artisans around Shantiniketan and the adjoining villages, even today. The finest of Kantha embroidery comes from Nanoor, 21 km from Shantiniketan in the Birbhum district of West Bengal. But the traditional quilt makers are a handful in the number who practise the original form of the needlecraft. The contemporary artisans use embroidery techniques used for quilt making to make diversified products. They do not recycle old fabrics but use new materials instead. These are by-products and not as exclusive as the old quilts.

Kantha embroidery is perhaps an integral part of every woman of West Bengal; however, as per a report from the website of wbmsme.gov.in, it is concentrated in the districts of Birbhum, Burdwan, Malda, Murshidabad, East Medinipur, North 24 Parganas and Kolkata. Among these districts, the premium Kantha comes from the Nanoor Cluster of Birbhum. Various outlets in Bolpur and Kolkata retail Kantha products. Several designers have adopted this needlecraft and given it a contemporary twist. Some of the finest quilts were available in the Gurusaday Dutt museum until it closed down to visitors recently. The museum pieces reflect upon the local life, belief and rituals of the makers. One can see them virtually at the Philadelphia Museum of Art that houses two of the finest collections donated by Stella Kramrisch, a historian who sourced them from India during her stay here as an academician.

Kantha making is practised only by women and helps empower more than 5000 artisans in West Bengal. Some of them with years of experience have taken up entrepreneurial roles. Every year the government honours distinguished Kantha artisans with national and state awards. Alima Khatun is a National Award Winner who practices in the rural areas of Birbhum supplying to the mass-market, while Mahamaya Sikdar and Bina Dey practice in the urban belt. They cater to exquisite commissioned products like quilts and wall hangings while training other artisans. Tajkira Bibi is a prominent and benevolent master artisan who has never applied for any award and remains an unsung hero. She impacts the lives of more than 200 women and helps them sustain a life of dignity.

The Nakshi Katha has undergone a transition over years of existence. It reflects the socio-cultural changes of our society. Kanthas magically knotted many families and communities together and travelled across borders. As we are aware that dynamics in economics bring about cultural diffusion, we find similar traits in the needlecraft of Kantha. Hence, craft connoisseurs question the future of the craft and wonders if it can be still called a ‘Kantha’ after diversifying into several end-products like a saree, stole, home linen, bag etc. It is apparent that from being a personal gift, painstakingly hand made over months for a beloved, Kanthas have transmuted and displaced from its original avatar. Commercial pieces no longer embody the ‘touch and tears’ of the maker and user. Nevertheless, the needlecraft has its distinguished reverence among craft enthusiasts as no two pieces are identical. The state of West Bengal holds a GI (Geographical Indication) for Nakshi Kantha till 2026.

Bibliography

- Zaman, Niaz. The art of kantha embroidery. Dhaka: The University Press, 2012.

- Basaka, Sila. Nakshi Kantha of Bengal. Kolkata, West Bengal: Gyan Publishing House, 2006.

- Ahmad, Perveen. Bangladesh Kantha Art In The Indo Gangetic Matrix. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Bangladesh National Museum, 2009.

- Sethi, Ritu, ed. Embroidering Futures: Repurposing the Kantha. Bengaluru, India: India Foundation for the Arts, 2012.

Top image: A contemporary Kantha with a geometric pattern made by a Muslim artisan. Source: Photographed by author in November 2019 at Nanoor, Birbhum, West Bengal. Permission was taken from the artisans before photographing them

Can I artisans details