Mitti ka kaam literally translates as “clay work” and its practitioners are commonly referred to as kumhar in Pakistan. It basically constitutes production of traditional terracotta utensils that are made throughout the length and breadth of the country—in remote villages and bustling towns and cities. Potters in each area produce distinct work not found anywhere else in the region such as the kaghazi (paper fine) pottery of Ahmedpur by Swali Mohammed’s family and the chit work (fine painted designs) produced in Badin by Muhammed Achar’s family. While one potter’s work does not represent the stylistic variations of wares produced by potters all over in Pakistan, it covers the basic production materials and technology.

A traditional potter’s workshop is ideally located within the house. In cities, one may also come across areas dedicated to the workshops mostly in the suburbs. The entire household of a kumhar including women, children and elderly contribute towards the work. A potter sources his materials from his surroundings, including a low firing terracotta clay, clays and pigments for surface decoration, readily available fuels such as animal dung, wood, dried grasses and industrial waste as seen in urban centres.

A traditional potter’s workshop is ideally located within the house. In cities, one may also come across areas dedicated to the workshops mostly in the suburbs. The entire household of a kumhar including women, children and elderly contribute towards the work. A potter sources his materials from his surroundings, including a low firing terracotta clay, clays and pigments for surface decoration, readily available fuels such as animal dung, wood, dried grasses and industrial waste as seen in urban centres.

Clay is normally sourced from nearby riverbed or land; it is first dried and then pounded into small pieces. Water is added to the clay and allowed to soak. Some potters sieve the crushed clay or the soaked slurry for better consistency. As clay hardens, it is wedged by foot or hand, sometimes tempered with organic materials or sand, and is ready for use. Forming methods vary depending on the work being produced. Most potters use a wheel and employ various throwing techniques, most commonly forms with heavy bases that are then chased into shape using a paddle and anvil. The handmade techniques usually include variants of coil and slab forming methods.

After a large body of work has been prepared and allowed to dry, it is coated with a layer of thin clay slip (astar) and decorated with pigments. The colours for decoration mostly include white, black and bright terracotta (laal). The pots are fired to about 800 degrees centigrade in a kiln. The methods of firing and kiln designs vary from one place to another; potters use open pit firing methods or purpose built brick kilns.

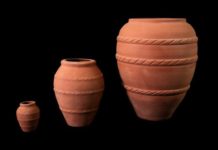

The most common vessels made by kumhars all over the country are the water containers, which come in various forms, sizes, surface decoration and different production methods. Some of its variations are matka, surahi, gharha, gagar, nadi, matti, kalsa, ghela and kooza. Apart from a predominantly vessel-based production, a kumhar also makes toys, stove, oven, oil lamp, khaprail (roof tiles) and some decorative items. When descriptions of the forming methods, decorative designs, kilns, fuels, tools and material from Indus Valley Civilization are compared to present day terracotta craft practices, we see stark similarities, which point to continuation of the ancestral craft over the centuries despite various influences.

The traditional terracotta pottery is on a decline in Pakistan as many traditional potters have either stopped working or are not passing on the craft traditions to the next generation. The terracotta is replaced by affordable plastic and durable metal containers. Yet the number of potters is so large that the craft survives to this day especially in areas where there is demand for the potter’s traditional products.