The intersection of art and the narration of religious tenets have an enduring antiquity in India. Evidence from the third century BCE attests to this manner of telling of tales through narrative devices including scrolls. These traditions include the bards in Rajasthan who recite the legendary exploits of the hero-gods with the unfolding of the phad scroll, the chitrakathis of Maharashtra, the Jadu-Patua of the Santhal tribes and the magic-realistic scrolls of the Nakashi in Telengana. A part of these continuing traditions are the pata chitra narrative scrolls painted by the Patuas or Chitrakars community from West Bengal.

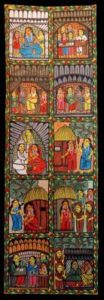

The itinerant Patuas, arrive literally at the doorstep or at local fairs displaying their long vertical pats (scrolls). The lengths can extend to 26 feet and the width between 1 to 2 feet. The Patuas not only paint the scroll using a combination of natural and synthetic paints, but also compose and perform. The patagaan story-sog is recited as the scrolls are unrolled.

The itinerant Patuas, arrive literally at the doorstep or at local fairs displaying their long vertical pats (scrolls). The lengths can extend to 26 feet and the width between 1 to 2 feet. The Patuas not only paint the scroll using a combination of natural and synthetic paints, but also compose and perform. The patagaan story-sog is recited as the scrolls are unrolled.

Their traditional audiences follow diverse faiths and customs, very like the Patuas themselves whose faith is a syncretic blend of both Hinduism and Islam. For the Hindus the pats tell stories from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, the Puranas, the Mangalakavyas. They recite stories ranging from sacred regional fables to morality tales, replete with punishments meted out to wrongdoers, to goings-on from more distant places. The pats on the legends of Gazi Pir are for those who follow the Islamic faith, while the Santhal and Bhumij tribal pats tell tales of their customs, legends and beliefs.

Over the past few decades, competition from other forms of entertainment had impacted the Patuas. However, since the 1990s the Patuas role have expanded to include communicators and educators, spreading social messages through their painted pats to rural audiences. The Patuas have seized the opportunity, acclimatizing their work to changing demand yet keeping within their traditions to serve wider audiences.