Returning from a campaign with Toyotomi Hideyoshi on the Korean peninsula, the feudal lord, Mori Terumoto brought back with him to Japan two Korean potters, Li Sukkwang and Li Kyong. It was these two brothers who were responsible some 400 years ago for doing work, which marked the beginnings of hagi-yaki.

When Mori Terumoto took up residence in a castle in Hagi, permission was granted to Li Sukkwang to build a kiln to make pieces of pottery, especially for the fief. The results were the first real pieces of Hagi Yaki. After Li Sukkwang died, his brother continued the work and the feudal lord of Hagi gave him the Japanese name Hagi Kouraizaemon, a name which continues to be used to this day.

Early pieces of hagi-yaki owed much to the style of pottery which was being made in Korea at the time. Gradually, however, such things as a raku or rustic character was added and this developed into a highly individual style, which is still in use today.

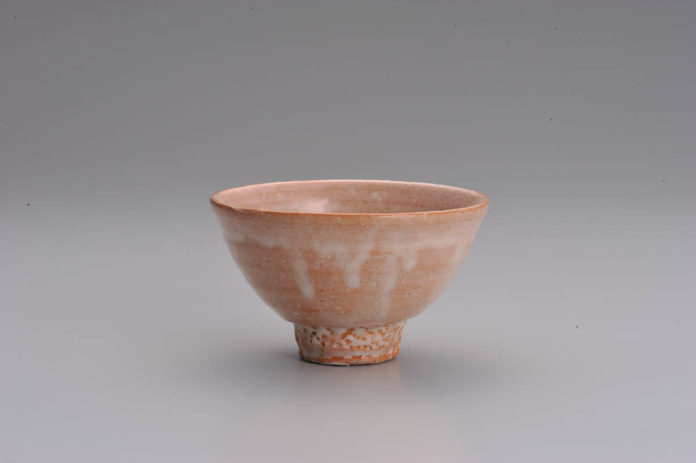

Perhaps its most distinctive feature is its rustic quality, which is partly the result of little shrinkage during firing. Added to this, the finished ware is highly absorbent. Being so absorbent means that gradually as a piece is used for tea or sake over the years, it becomes stained and changes colour. It was this phenomenon which was particularly admired by tea aficionados and was termed cha-nare, literally meaning “tea maturing”, indicating that as a piece is used, it takes on an aesthetically pleasing matured appearance. Another characteristic is the simplicity of forms and decorations. In most cases, the pieces are not painted. Since the blend of clay used, glazing conditions, spatula marks, etc., will all produce various patterns as a consequence of being baked in ascending kilns, all pieces are designed to make the best use of this peculiarity.

Another feature is its simplicity of form and decoration. In fact, Hagi Yaki almost never has any under- or over-glazing painted decoration. Instead, its true appeal comes from the way the potter makes full use of what effects he or she knows can be expected during the firing in a noborigama or “climbing kiln”. This is especially true of how various combinations of clay will react, the application of glazes, and marks made with modelling tools.

The main items produced these days include various types of ornaments, pieces of tableware, vases, and cups, bowls and pots for tea.

Mishima-tsuchi clay and a local clay called ji-tsuchi clay are added to the main ingredients, Daido-tsuchi clay and mitake-tsuchi clay, to create a pottery clay for manufacturing the pots. After the clay has been moulded into pots by a variety of methods including turning on a potter’s wheel, moulding by hand, tatara, etc, engobes, inlays and engravings are applied and the pots are bisque-fired. After bisque-firing, glaze is applied. After the pots have been glazed with a transparent or white glaze, they are then baked in an ascending kiln. Once in the kiln, the glaze tone on the parts that come into direct contact with the flame changes; this change is referred to as “yohen.”

Further reference

Yoko Akama and Yoko Ozawa Full of emptiness: The wonder of Hagi ware Garland, 2/12/2018 (source of images)

This entry is referenced from the website of The Association for the Promotion of Traditional Craft Industries.