Melanesian pottery has a long history going back to Lapita pieces uncovered by archaeologists.

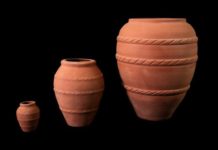

Shapes, sizes and usages of pottery are diverse and widely dispersed. Objects range from small sculptural pieces to huge cooking and storage pots. Local clays shaped through coiling techniques, when dried, were simply open fired.

Traditional pot making cultures were quite productive. Pottery featured in some famous trading rings. On Hiri voyages, Motu peoples from around Port Moresby sailed to their Papuan Gulf partners, exchanging pots in return for sago and logs.

Activity in some famous pottery areas waned or ceased long ago. Elsewhere, viable operations continue to evolve and prosper. Pottery, like Mary Gole’s distinctive modern works inspired by her cultural heritages, are in gallery collections. Miniature ceramic ‘Mudmen’ masks, plates, mugs and vases from Goroka, Eastern Highlands, get sold to tourists.

Often utilitarian wares with plain surfaces would just be given characteristic forms. Elsewhere objects got decorative flourishes or incised patterns. In some places, fired pots were also painted.

CHAMBRI pottery

Aibom Island in Chambri Lake, on the Sepik River, was central to a long flourishing traditional trading ring. Local patronage continues, but is validated by overseas collecting.

Legends and festivities celebrate their communities’ good fortune in having an ample supply of superlative clay and women ancestors who passed down pottery skills. Female Chambri potters are individual artists with personal styles and focus. This is demonstrated across time in the 1930s pieces in museum collections, pieces bought in 1973 and those seen today.

Utilitarian objects are mainly produced, but each piece is made as an individual work of art. Finials featuring chicken forms sit and cover thatch joins along house ridges. Faces and scalloped edges are incorporated onto pots or containers. Decorative bands and motifs are often painted onto fired pots in one or two colours.