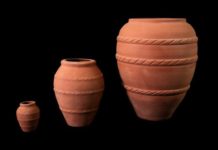

In history and archaeology, ceramics are important artefacts that can be dated through scientific methods to offer insight into the development and cultural diversity of a society. Thai ceramics can be categorized into the following periods:

In prehistory (2,500-10,000 years ago), shards of pottery made of coarse clay, decorated with a variety of patterns and fired at low temperatures have been found at different sites. At Tham Phi in Mae Hong Son province, ceramics with distinct forms such as tripod vessels, tray with pedestal and pots have been found. At Ban Kao in Kanchanaburi province and Ban Chiang in Udon Thani province, some of the pottery found includes large wide-mouthed pottery, round-bottomed vessels and footed pottery. These containers were low-fired pottery in grey and orange-brown, painted or plain. The paints were red and white, bearing animal, geometric, spiral, and curved patterns.

Ceramics can be found in different periods. Dvaravati ceramics (seventh to eleventh centuries) include carinated pottery, round- bottomed pottery, jars, bowls, pots with spouts and dishes with tall petals. The clay is red or dark- grey brown. Decorations were made by incising, painting, burnishing and impressing.

Regarding Lopburi ceramics (eleventh to fourteenth centuries), kilns were discovered at Ban Kruad, Buriram province, along with tall-shaped pottery such as urn jars, jars with small handles, tray-like bowls, kettles and boxes, particularly made into different animal shapes. The ceramics were made of ordinary clay and high-fired, glazed or unglazed. A later advancement was coating with the mixture of ashes of different plants.

Ceramics from the Sukhothai period (fourteenth to sixteenth centuries) reflect the result of Sukhothai’s prosperity on its ceramic production, made for local consumption as well as export. Ban Pa Yang and Ban Ko Noi in the old Sukhothai city, and Mueang Chaliang, Sawankhalok, were major production bases. Most of the ceramics were utensils such as dishes, bowls, jars, vases and boxes. They were both low-fired and high-fired, glazed and unglazed. Meanwhile, architectural decorations include tiles, pipes, pan lom (gable ends), and balustrades. One prominent type of ceramics from this period was celadon.

Lan Na ceramics (around the fifteenth century) can be found in many ancient kiln remains across Northern provinces. The Wiang Ka Long ceramic tradition was found at Wiang Pa Pao district in Chiang Rai province and Wang Neua district in Lampang province; the San Kamphaeng tradition was found in Chiang Mai province; and the Phayao- Phan tradition was found in Chiang Rai province. Most of these ceramics were coated by clear green glaze and fired at high temperature. These were mainly containers, such as dishes, bowls, cups, boxes, vases and jars. There were also lamps and small Buddha and animal sculptures.

Because of the disintegration of the ceramic industry in Sukhothai, Ayutthaya began to order ceramics from China for use in the court. In 1600 Ayutthaya began to produce its own ceramics by building kilns in Sing Buri province. The most important one was the Mae Nam Noi Kiln in Bang Rachan district, producing ceramics for local consumption and export. Its major product was the jar with four handles. In the late Ayutthaya period in the mid-eighteenth century, the kingdom ordered from China bencharong ceramics with Thai designs and white chinaware with blue designs.

In the reign of King Rama II, utensils for royal use, such as dishes and bowls, were ordered from China with Thai craftsmen overseeing the design. Rattanakosin ceramics included bencharong ceramics with thep phanom (deva clasping hands in worship posture), garuda (mythical bird), kinnari (half-bird half-woman) and sing (lion) designs within a kankhot (curled plants) motif. King Rama III ordered the construction of a thu riang kiln at Saket Temple to make roof tiles and colour-coated tiles. During King Rama V’s prosperous reign, ceramics were imported from China, Japan and Europe, and Thailand also began to set up factories producing coarse-grained ceramics, glazed and unglazed, such as tea pots, water jars, basins and jars.

Today, advanced technology has enabled the Thai ceramic industry to cater to the local and international markets. The ceramic arts also sees biannual national competitions in which artists and designers create more contemporary ceramic arts and designs. Meanwhile, major production bases that continue the old ceramic traditions still preserve their uniqueness.

Contemporary ceramics in the Benjarong style, by craftsmen of the Office of Traditional Arts, Ministry of Culture